Pierre Klossowski

Incommunicables

Organised by Jürg Haller & Daniel Horn

21.9. - 15.11.2019

Pierre Klossowski, Les Incommunicables

Pierre Klossowski, Les Incommunicables

Pierre Klossowski, Les Incommunicables

Pierre Klossowski, Les Incommunicables

Pierre Klossowski, La chorale, 1991, Colour pencil on paper, 177 x 150 cm

Pierre Klossowski, La Chiromancienne, 1986, Colour pencil on paper, 150 x 102 cm

Pierre Klossowski, L’auberge de la comète, 1983, Colour pencil on paper, 198 x 150cm

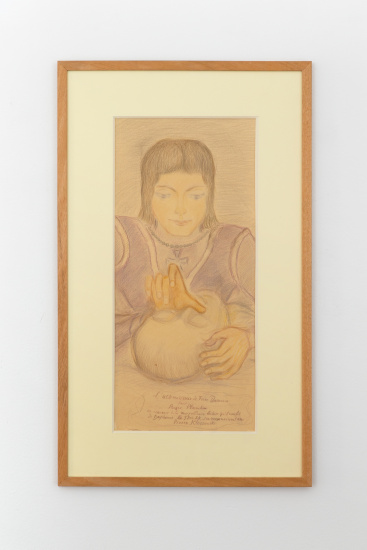

Pierre Klossowski, L’ultime vision de frère Damien II, 1985, Colour pencil on paper, 88 x 52 cm

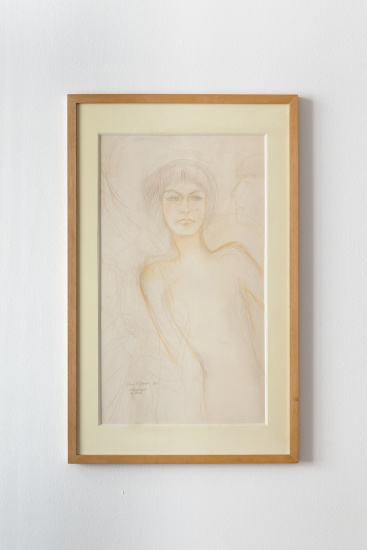

Pierre Klossowski, Tadzio (autoportrait de l’artiste), 1987, Colour pencil on paper, 100 x 62.5 cm

Pierre Klossowski, Roberte partagée entre ses esprits, 1979, Colour pencil on paper, 175 x 100cm

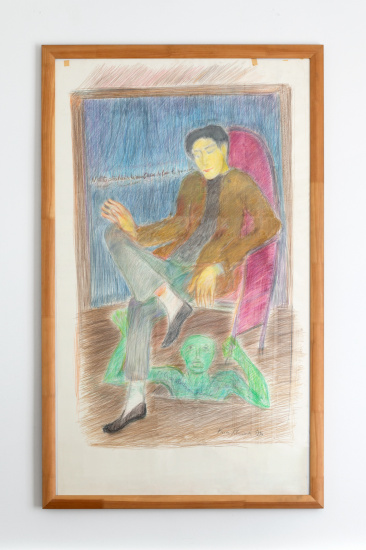

Pierre Klossowski,

N’as-tu pas honte vieux Cacus de faire la grenouille, si tu m’abandonnes Gabriel je crève,

1994, Colour pencil on paper, 170 x 104 cm

Klossowski took up drawing professionally from the late 1960s onwards, save for an intimate debut exhibition in 1955 held at his brother Balthus’s Paris studio. He was over sixty at the time, positively part of the French literary establishment, albeit somewhat under the radar—an author’s author, for Foucault, Deleuze, Guattari, and one imagines many lesser names within his circle. The drawings he exhibited were not only systematically repetitious and strange but awkward; here was an erudite scholar and writer on ancient Christian doctrine, on Nietzsche and Sade, producing these at first black and white and soon cheery coloured pencil drawings, some of them two meters tall, picturing what or whom exactly?

Closeted scenes, into which Klossowski placed and ever so slightly estranged and commingled key figures from his life: the paternal-pederastic novelist André Gide he interned for as a teenager; his avant-garde days ally Georges Bataille; his revered heroine wife Denise Morin-Sinclaire, a concentration camp survivor he re-envisioned as the libertine Roberte; and finally, his younger selves rejuvenated as wispy twinks. Frequently, these characters are further expanded and tripled to become the pagan goddess Diana, Knights Templars or an adopted alter-ego from a Thomas Mann novel, as is the case in Tadzio (Autoportrait). Talk about auto-fiction? Hardly. At least not of the Chagall-strange kind. Decryption rather than revelation. Not of nightmares or dreams, but of glyphs; stereotypes; codes.

Many of Klossowski’s figures’ legs, arms, profiles, elbows, hands, extremities are angled and engaged, to the extent of discomfort, or at least slight disapproval. The faces, in contrast, hardly ever change, from placid to piqued, to slightly amused—some kind of flirting. There is no sign of ageing anywhere because there are only roles, stand-ins—simulacra in the sense of Klossowski’s thinking about the human as bodies; more, but not really dramatically more than excitable, cognisant flesh: all impulses, all movement, sometimes smooth, sometimes rougher, navigating and submitting to transactional systems of supply and demand. Fluid tautness—mannequin- or mask-like—not quaint individual expressiveness, Klossowski intuited in the 1970s, would be a value and become a standard in the dawning postindustrial media regimes.

The drawings resemble Dos and—mostly—Don’ts storyboards for an in-company or campus training session, mischievously queered, camped up, gone out-of-hand. Diligent anatomies of indiscretions rather than slickly appropriative critiques of popular culture’s surfaces, objects and idols—this is where the works’ peculiar topicality arises from, be it #metoo, polyamory or church abuse scandals. Bourgeois and institutional transgression, for better and for worse, occurs on the level of the everyday, in the dirty business of, well, doing all kinds of business. Klossowski’s drawings frame the extra in the ordinary.

Daniel Horn